Dec 9th 2022 – Jan 28th 2023

“A photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.” Susan Sontag

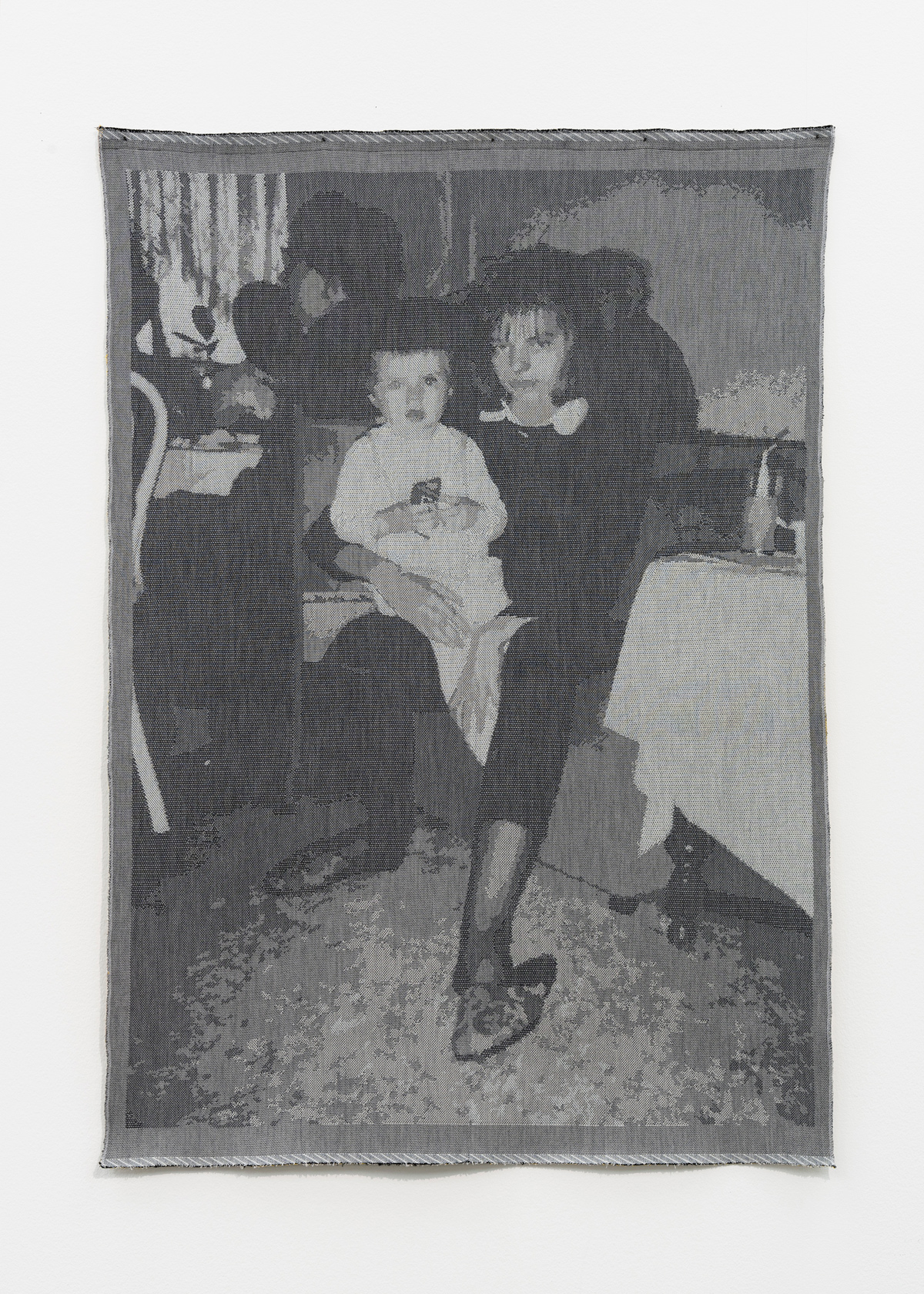

Der Diskurs über die der Fotografie stets inhärenten Anhaftung der Spur ist so alt wie die Fotografie selbst. Und doch ist er in Anne Pöhlmanns sechsten Einzelausstellung bei Clages so aktuell und evident wie nie zuvor. So wie Barthes einst die Einschreibung der visuellen Spur postulierte, so stellte er in diesem Zuge eine Verbindung zwischen Fotografie und Mutterschaft her. Das indexikalische Verhältnis von Fotografiertem und Rezipient:in gleiche dabei „einer Art Nabelschnur“, die den dargestellten Körper des fotografierten Objekts mit dem Blick des Betrachtenden beinahe symbiotisch verbinde. Mit Comforters setzt sich Pöhlmann nicht nur mit ihrer fotografisch künstlerischen Praxis, sondern ebenso mit ihrer neuen Mutterrolle auseinander und legt – teils malerisch abstrakt – persönliche Spuren der vergangenen Jahre ihres Lebens offen.

Von vielen Berufskolleg:innen als unmöglich propagiert, ist die Vereinbarkeit von Künstlerinnendasein und Mutterschaft tatsächlich auch im 21. Jahrhundert immer noch eine sozio-ökonomische Herausforderung. Von mangelnder Rücksichtnahme bis hin zu offener Ablehnung ist die Negierung des Mutterseins durch ein prekäres, u.a. von Abramović propagiertes Glaubenssystem allgegenwärtig. In Comforters verknüpft Pöhlmann diese (durch ihre Weiblichkeit) eher „soft“ konnotierte Problematik mit der „Härte“ der technischen Möglichkeiten der digitalen Fotografie.

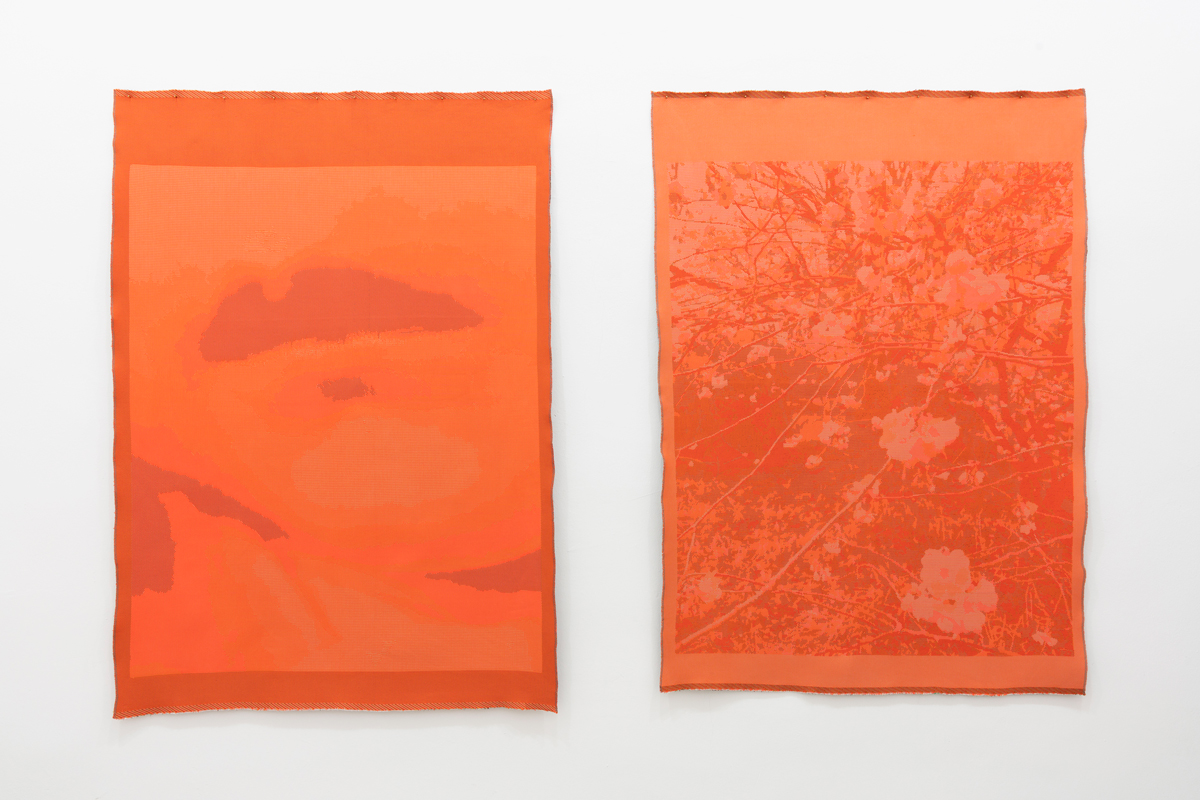

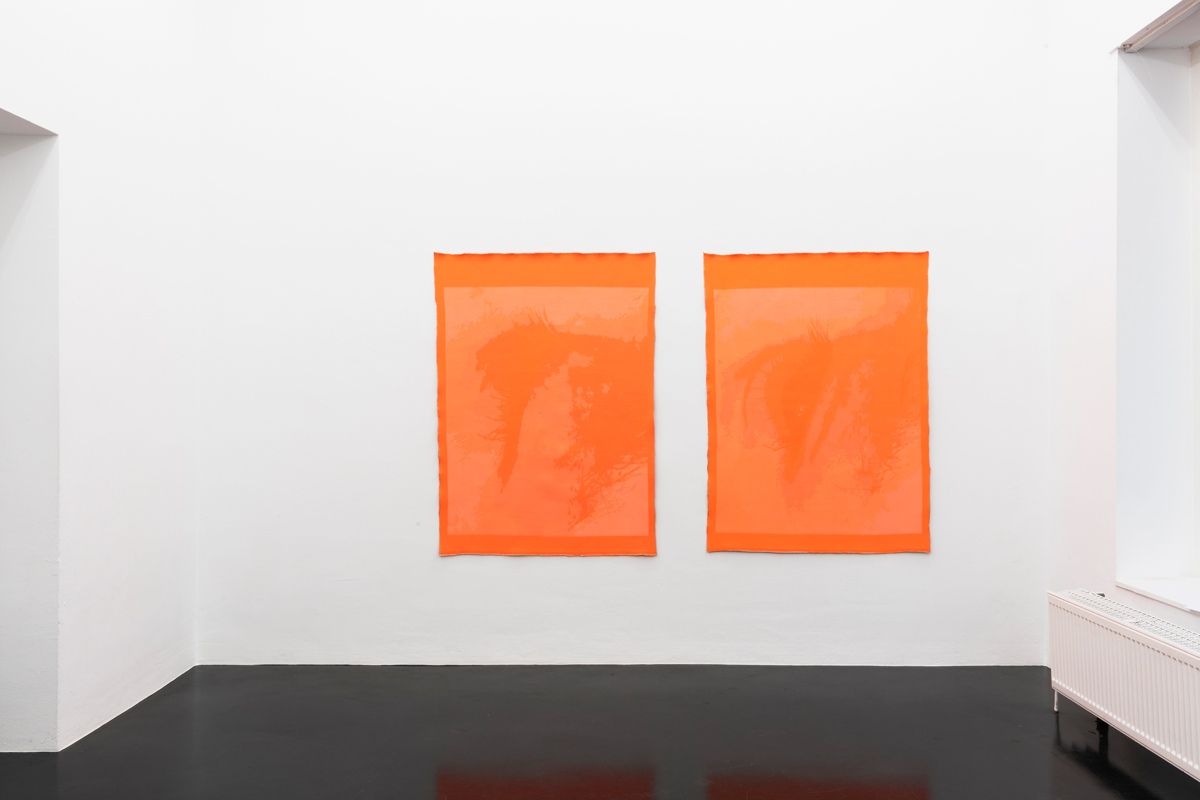

Obschon sich in der analogen Fotografie tatsächlich ein körperlicher (Licht-)Abdruck als physische Reaktion der Leuchtdichte eines Objektes auf der chemischen Oberfläche des Bildträgers „abdrückt“, wird diese Körperlichkeit in Pöhlmanns digitaler Praxis alles andere als obsolet. In ihrer konzeptuellen Auseinandersetzung mit den technischen Neuerungen und Möglichkeiten der Fotografie untersucht sie deren stetig neu zu verhandelnden mechanistischen Abbildungsprinzipien sowie ihr Verhältnis zu einer wie auch immer gearteten Materialität. In Comforters geht Pöhlmann über die zweidimensionale Reproduktion hinaus und nimmt sich erneut der digitalen High-Tech-Welt der Bildbearbeitung an, indem sie hochmoderne Strickmaschinen als „Entwickler“ ihrer Arbeiten nutzt. Dabei geschieht die Generierung digitaler Bildpunkte über die gezielte Aufschlüsselung von Pixeln und Codes in Raster, Grids – eine Thematik, mit der sich die Künstlerin bereits seit über zehn Jahren beschäftigt. Durch die vierschrittige (Nach-)bearbeitung der meist mit dem Handy festgehaltenen Lebensmomente werden die digitalen Informationen in ein maschinenkompatibles Raster übersetzt. Die Strickmaschine, die – ähnlich wie die Technik des Webens – in ihren Mustern erste Formen des modernen Computings repräsentiert, übernimmt schließlich die (Rück-)Übersetzung in menschenlesbare Bilder. Den Betrachtenden begegnen Szenen des Familienglücks, aber auch scheinbar abstrakt anmutende Ansammlungen von Rasterpunkten, gehalten in orange-gelben Neontönen.

Die ausgestellten Fotografien und ihre bildlich manifestierten Momente einer vergangenen Realität haben möglicherweise nicht nur Spuren auf ihrem Bildträger hinterlassen. Ob der Titel der Ausstellung sowie die physische Manifestation der Bilder in dicken Strickdecken an materielle „Comforters“ im Sinne wärmender Bettdecken oder in ihrer direkten Übersetzung an Baby-Schnuller oder andere komfort- und trostspendende Dinge erinnert, Comforters eröffnet eine Bandbreite an Assoziationen und ausgelegten Spuren. Und Spuren sind da, um gelesen zu werden.

The discourse on the attachment of the trace which is always inherent in photography is as old as photography itself. And yet, in Anne Pöhlmann‘s sixth solo exhibition at Clages, it is as current and evident as never before. Just as Barthes postulated the inscription of a visual trace, he posited a connection between photography and motherhood in the same vein. The indexical bond between the photographed and the recipient resembles „a kind of umbilical cord“ that almost symbiotically connects the depicted object with the gaze of the viewer. With Comforters, Pöhlmann not only explores her photographic-artistic practice, but also her role as a new mother and reveals – often in a painterly abstract way – personal traces of the past years of her life.

Propagated as impossible by many professional colleagues, the compatibility of being an artist and a mother continues to be a socio-economic challenge well into the 21st century. From disregard to outright rejection, a systemic and precarious belief system resulting in an outright negation of motherhood propagated by Abramović a.o, is ubiquitous. In Comforters, Pöhlmann links this “softly” connotated problem (due to its link to femininity) with the “hardness” of the technical possibilities offered by digital photography.

Although in analog photography a physical cast (of a light) is indeed „imprinted“ as a physical reaction of the luminance of an object onto the chemical surface of the image carrier, this corporeality becomes anything but obsolete in Pöhlmann‘s digital practice. In her conceptual exploration of the technical innovations and possibilities of photography, she examines its mechanistic principles of representation, which are constantly being renegotiated, as well as its relationship to a materiality of all kinds. In Comforters, Pöhlmann goes beyond two-dimensional reproduction and once again takes on the digital high-tech world of image processing by using ultra-modern knitting machines as „developers“ of her works. In doing so, the generating of digital pixels occurs via the targeted breakdown of patterns and codes into grids – a theme the artist has been exploring for more than ten years. Through the four-step (re)processing of personal moments, mostly captured with a cell phone, the digital information is translated into a machinecompatible grid. The knitting machine, which – similar to the technique of weaving – represents in its patterns the first forms of modern computing finally takes over the (re)translation into human-readable images. The viewer encounters scenes of family happiness, but also seemingly abstract accumulations of grid points, held in orangee-yellow neon tones.

The exhibited photographs and their pictorially manifested moments of a past reality may have left traces beyond their visible image carrier. Whether the title of the exhibition or the physical manifestation of the images in thick knitted blankets remind us of physical „comforters“ in the sense of warming bedsheets or in their direct translation of baby pacifiers or other comfort and consolation giving things, Comforters opens up a range of associations and laid out trails. And traces are meant to be read.